Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

The daughter of Andrée Sarah Oestreicher and Léon André Vaudecrane, Jacqueline Vaudecrane was born November 22, 1913 in Paris, France. She grew up in a devout Roman Catholic household. Her father was a pilot with the Aéronautique Militaire during The Great War and the publisher of a leading business newspaper, "L'Exportateur français: grande revue mondiale d'informations, de défense et d'expansion des intérêts français". Her mother was the editor of a fashion magazine.

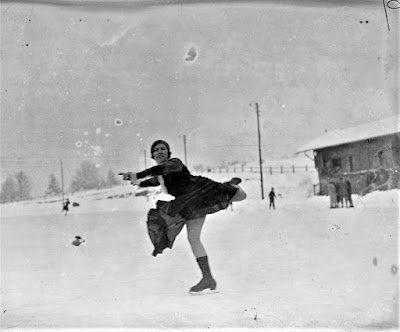

Photos courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

When Jacqueline was seven, her father took her to The Salon d'Automne, which was near the Palais de Glace at the Champs Elysées in Paris. As they passed the rink, she begged her father to take her skating. She was on the ice the next week and soon Andrée Joly, who trained there among the masses with partner Pierre Brunet, recognized she had potential and told her father so.

Andrée Joly, Pierre Brunet and Jacqueline Vaudecrane. Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Léon Vaudecrane, a very strict man, had other plans for his daughter. At one point, he signed Jacqueline up for piano lessons and demanded she stay at home and practice all day. After much protest, she convinced him to let her choose skating instead. The reasoning behind her choice was simple. She just wanted to be outside.

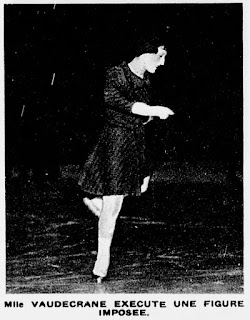

Photos courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

Andrée Joly and Pierre Brunet took Jacqueline under their wing during the roaring twenties, taking her along on trips to St. Moritz and Davos, where she became accustomed to training in sometimes brutal conditions on outdoor ice. She learned figure skating through imitation and reading from Pierre Brunet's Austrian skating manual.

Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

Interestingly, one of Jacqueline's first victories on the ice wasn't in a figure skating competition, but in a speed skating race. In 1925, she took first prize in the 'course de fillettes' class in a five hundred meter race held at the Palais de Glace. She won her first medal at the French Figure Skating Championships, a bronze, in 1931 and made her inauspicious debut at the European Championships in Paris in 1932, placing dead last on every judge's scorecard. Four years later, she was sent to the European and World Championships, where she fared just as worse - placing sixteenth and fifteenth.

Around this time, Jacqueline was studying fashion in Versailles. Her father, whom she once described in an interview so kindly transcribed by Lauren Tress as "very eccentric... with strange ideas", told her she was a terrible skater and drove her to quit skating for three years. Out of the blue, it was he who asked her if she'd like to start skating again. It turned out that he'd struck up a friendship with Pierre Brunet. When she returned to the ice, she found that all of her peers had progressed in their skating. She of course hadn't and the experience was understandably frustrating.

Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

In the July of 1936, Jacqueline married Marcel Boussoutrot. Pierre Brunet, by then an Olympic Gold Medallist in figure skating, and Roger Ducret, an Olympic Gold Medallist in fencing at the 1924 Summer Olympic Games, stood for her at her wedding.

From 1936 to 1938, Jacqueline won the French junior title followed by two French senior titles - victories she had strived for fiercely after skating in the shadow of Gaby Clericetti for several years. Unfortunately, her competitive career ended with a fizzle rather a bang. In 1939, the Fédération Française de Patinage sur Glace decided to open up the French Championships to foreign skaters. She was furious when she lost to an unheralded Belgian skater. After placing fourteenth at the final World Championships held before World War II broke out, she quit in utter frustration and decided her passion for figure skating could be put to a better use - setting up an elite skating school. It was a daring decision, as at the time figure skating was largely viewed in France as more of a fashionable pastime than a serious competitive sport and there were few dedicated skating coaches in the country. Her own mentors, The Brunet's, had already left to pursue professional careers in North America.

Before almost all of France's indoor rinks closed their doors during World War II, temporarily putting an end to figure skating in the country, Jacqueline and a small group of skaters would cross the demarcation lines in Nazi-occupied Paris to go skating in Chamonix. "One day it happened," recalled Jacqueline. "The Germans had also invaded our skating rinks."

Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

Jacqueline's husband's cousin, aviator Lucien Bossoutrot - a fighter pilot during The Great War - was interned in Vichy in 1943 for his opposition to the Nazi occupation. He fled after fifteen months of imprisonment and joined the Resistance. During the final year of the Nazi occupation, Jacqueline was appointed France's 'national monitor' for figure skating and sent to Chamonix to scout talented young skaters. Her first group of students, which included Huguette Gay-Couttet, Monique Schmidt and Thérèse Tairraz, never really had the chance to further their skating careers because of the War.

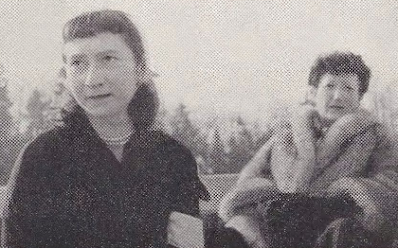

Top: Jacqueline du Bief and Jacqueline Vaudecrane. Bottom: Jacqueline Vaudecrane (right) with a group of her students in 1952. Left to right: Claude Daury, Liliane Madaule, Claudine Baulande, Maryvonne Huet, Monique Schmidt, Alain Giletti, Alain Calmat, Michèle Allard and an unidentified skater. Photo courtesy "Skating World" magazine.

After the War, Jacqueline became a mother and taught at the Molitor and Rue Saint-Didier rinks in Paris. A trip to England opened her eyes to the possibilities of skating in France. Impressed by the strength and numbers of British women coming up the ranks, she decided that improving skater's school figures would be the key to taking them far. Upon her return to France, she convinced the rink's employees to flood the ice more often so that her students would have fresh patches to work on.

Jacqueline du Bief, Jacqueline Vaudecrane and Liliane Madaule at the Molitor rink in 1949. Photo courtesy "The Skater" magazine.

One of Jacqueline's first elite level students was Jacqueline du Bief, whose coach at the Victor Hugo rink - Monsieur Lemercier - had been taken prisoner and sent to Germany during the War. In her book "Thin Ice", Jacqueline du Bief recalled, "Madame Vaudecrane, who was called by her pupils Jacqueline, Clicline or 'patronne', was a little woman with a head of thick, black curly hair, cut short like a boy's, a pair of grey-green eyes that were never still, and an air of authority and resolution. Enthusiastic, choleric, and always over-excited, she had the greatest confidence in herself and her work and no obstacles deterred her. Thus, we used to see this new teacher, who was gifted with the most extraordinary energy, run behind her pupils, all the time shouting corrections at the top of her voice in order to waste no time and the better to urge them on... [She] had realized from the beginning of her career as an instructor that it was a mistake to make things too easy for pupils and to tell them every little thing. She knew that it was much better to make an appeal to their intelligence and to make them think for themselves. Half her teaching was based on the pupil's personal work, and in view of my independent temperament, this method suited me admirably." Jacqueline du Bief made history in 1952 as France's first World Champion and Olympic Medallist in women's figure skating. Jacqueline Vaudecrane credited her pupils success to, above all things, her "iron will".

Jacqueline set up shop at the newly-opened rink at Boulogne-Billancourt in 1955. She coached Alain Giletti and Alain Calmat to the World titles in 1960 and 1965 and was worked with the first two French ice dance couples to medal at the European Championships - Christiane and Jean-Paul Guhel and Brigitte Martin and Francis Gamichon. Over the years, she also worked with Patrick Péra, Denise and Jacques Favart, Liliane Madaule-Caffin, Colette Laurandeau, Jacques de Beaumont, Janine Cartaux and her daughter Joëlle, Robert Dureville, Didier Gailhaguet, Anne-Sophie de Kristoffy, Laetitia Hubert and Surya Bonaly. She had no regrets about starting skaters young because she was of the belief that technique came easier than musicality. The more time she had with a skater, the more they could develop in both respects.

Didier Gailhaguet and Jacqueline Vaudecrane. Photo courtesy "L'Équipe".

Passionate and tough as nails, Jacqueline earned the nickname 'The Boss' from her students and certainly wasn't afraid of pushing the boundaries of the sport. After hearing Arnold Gerschwiler criticize a Czechoslovakian woman who included a double loop in her program for being 'unladylike', she decided to stick it to him by adding the even harder double Lutz to Jacqueline du Bief's bag of tricks. She costumed Alain Giletti in a red suit at a time when men, with few exceptions, dressed conservatively in black or grey. Cringing grey-haired French officials remembered the 'rouge' all too well. Jacqueline herself had donned a scarlet dress back in 1934.

Jacqueline also devoted considerable time and effort to developing her skater's on-ice personalities, prioritizing musical appreciation and artistic expression. She was all on board for her students being sent to America to work with the Brunet's if it bettered their chances of winning and by the accounts of her students, was sometimes more nervous about the results than they were.

Coaching Alain Giletti and Alain Calmat at the same time had its moments for Jacqueline. The two talented young men were very competitive and didn't always listen to her orders. At the 1954 World Championships in Paris, she was sick and had to spend a lot of time at her hotel. The two Alain's snuck off and attended a fun fair against her wishes. Another time, she insisted that all of her students wear tights "to improve body expression". Alain Calmat refused at first. Then he saw how well Alain Giletti was skating in them and changed his tune.

Jacqueline's students all had a great respect for her. Alain Calmat once remarked, "She's never mean, she never sacrifices one student for another, and I think that’s very important because it’s very rare." Alain Giletti recalled, "She was really a mother hen for me. She cared about my business, my equipment, how I washed up when I was very young." Patrick Péra described her as "a little piece of woman, always the first on the ice, never sick. A mother hen sometimes, very hard, demanding, sometimes uncompromising too." One example of this 'uncompromising' determination was a story that appeared in Jacqueline du Bief's book "Thin Ice". She recalled, "Arriving late to the little [train] station [in Chamonix] after some rather complicated adventures, what was my surprise to find Madame Vaudecrane on the line, gesticulating wildly in front of the engine. Seeing that I could not arrive before the train left, she had put forth all her charm and her energy to persuade the stationmaster to hold it up for me. In doing this, she had not hesitated to jump down on the track, despite the protests of that good man, and the train - which was composed of a single carriage in which we were the only passengers - was still in the station when I at last arrived!"

Jacqueline Vaudecrane, Didier Gailhaguet and Patrick Péra

A fun fact about Jacqueline is the fact she had a green thumb... and a very unique garden at her country home. When each of her students won a title, they gave her a tree as thank you. When Alain Calmat won the World Championships in 1965, she got a weeping willow. When Christiane and Jean-Paul Guhel medalled at the European Championships, they gave her a Japanese cedar. As her students accumulated medals, she accumulated shrubbery. She also enjoyed needlework and would show guests to her home the pieces she'd made while travelling abroad to figure skating competitions, proudly saying, "These are my school figures!"

Jacqueline was honoured by the French government in 1984 as a recipent of the Legion Of Honour, the highest French order of merit for military and civil achievements. It was presented to her by her student Alain Calmat, who was then the Minister Of Sports. She officially retired from coaching in 2001 at the age of eighty-eight. She passed away on February 27, 2018 at the incredible age of one hundred and four in the small town of Uzès, just outside the ancient village of Saint Quentin-la-Potèrie in the Gard department of southern France.

Less than a decade before her death, Jacqueline said, "I had no teachers. I worked alone. It was difficult. So, if I hadn’t received much, I would give to others. Evidently, whenever I have a World Champion, I don’t compare myself that I was never World Champion. I think it's good for a sports instructor to have not ever been a grand champion."

Skate Guard is a blog dedicated to preserving the rich, colourful and fascinating history of figure skating. Over ten years, the blog has featured over a thousand free articles covering all aspects of the sport's history, as well as four compelling in-depth features. To read the latest articles, follow the blog on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube. If you enjoy Skate Guard, please show your support for this archive by ordering a copy of figure skating reference books "The Almanac of Canadian Figure Skating", "Technical Merit: A History of Figure Skating Jumps" and "A Bibliography of Figure Skating": https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/p/buy-book.html.